- We follow up our brief initial comments in last week’s AM Call with a detailed discussion of potential restructuring

- The process of sovereign debt restructuring can be protracted and difficult, as seen in prior cases such as Argentina

- There are multiple interested parties that may be involved in a Venezuela/PDVSA debt restructuring process, including official representatives from the Venezuelan government, existing holders of defaulted bonds, multi-national lending organizations such as IMF and World Bank, direct lenders such as China, and other claimants such as corporates with pending claims against the prior Venezuelan government; the U.S. government may take on an active in negotiations

- We outline potential steps for a restructuring process and highlight challenges in removing holdouts from the bond renegotiation phase

- The current optimism on bond values may face a more sober reassessment of the practical difficulties in welcoming Venezuela back to the global capital markets

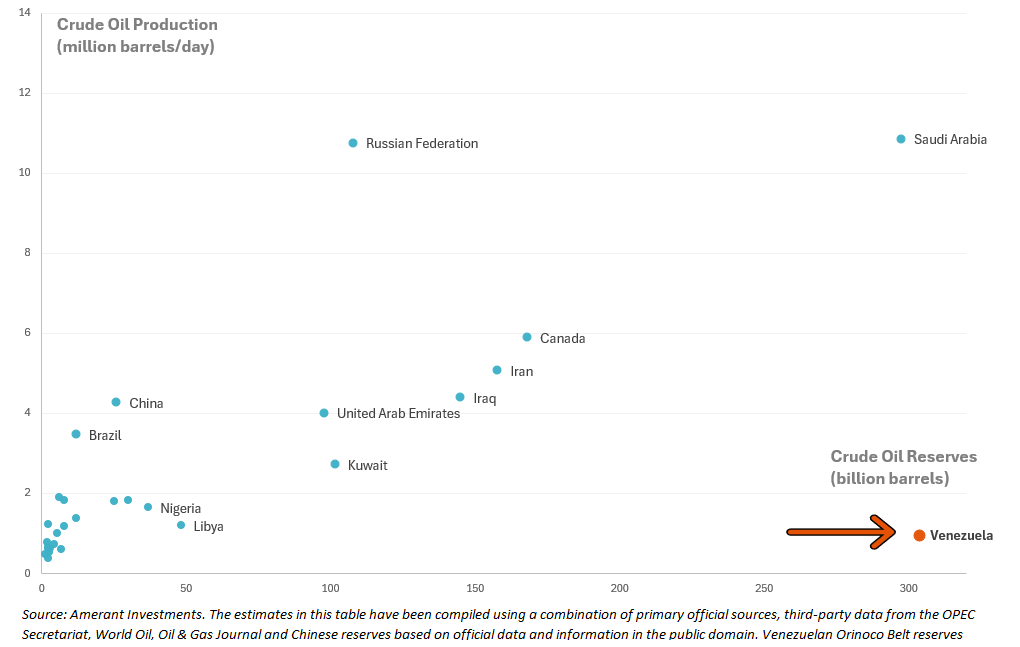

- The country’s significant oil reserves and the strategic interest of the U.S. are major positives for the potential for the outcome to move more quickly

Last week’s AM Call included Amerant’s first take on situation in Venezuela. In our report, we highlighted the broad rebound in market prices for Venezuelan debt instruments: https://www.amerantbank.com/ofinterest/theamcall-01052026/ and https://www.amerantbank.com/ofinterest/es/theamcall-01052026/

As a follow-up, in this report we outline the potential necessary steps for a restructuring in Venezuelan debt. We emphasize that the process could be lengthy and contentious. We are optimistic that the U.S.-led extraction of Maduro is only the first step in a broader strategic embrace of Venezuela by the U.S. If so, the U.S. may demonstrate interest in facilitating renegotiation and restructuring of Venezuela’s defaulted bonds (both sovereign and Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (“PDVSA”)) along with its pledge to support the country’s industrial and energy infrastructure and rebuilding.

Importantly, we believe that both the U.S. strategic interest and the country’s large oil reserves are key variables that could allow for 1) a more favorable restructuring timeline and 2) better recovery prospects. We do not rule out that the U.S. government could provide loans and/or guarantees, facilitate or fast-track credit committees, try to effect a “cram down” that essentially bypasses the “normal” restructuring process and protocols outlined below. We note the graph below shows the enormous potential of Venezuela to ramp up production relative to its oil reserves.

We expect that a practical restructuring solution is likely to include income-linked securities, such as GDP or oil-revenue warrants, basically acting as an “equity kicker” for the debtholders as a sweetener in addition to the renegotiation of specific bond terms. So the good news for recovery prospects is that Venezuela is a resource rich country, and, with the right framework, leadership, and patience, the country is capable of generating substantial government revenue to entice a global restructuring settlement. That said, we have not assigned a specific recovery value for the bonds, as we believe the outcome remains too uncertain to have any clarity on this metric.

Below, we outline the process and steps necessary to accomplish a debt restructuring for the Venezuela and PDVSA complex.

Preconditions and Required Steps for an Orderly Restructuring of Venezuelan and PDVSA Debt

Venezuela sovereign and PDVSA defaulted bonds have face value of over $75 billion. When adding other obligations such as additional PDVSA debt, bilateral loans, and arbitration awards, we estimate Venezuela’s total external debt is much larger, at $160 billion to $180 billion[1], depending on how accrued interest and court judgments are counted. We note that the most recent IMF estimate of Venezuela’s GDP is approximately $83 billion, implying a debt to GDP ratio of about 200%.

For claimants to receive compensation from Venezuela, multiple political, legal, institutional, and economic steps are required to achieve an orderly restructuring of the external debt of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and PDVSA. Given the country’s prolonged default since 2017, the presence of U.S. sanctions, and the complex creditor landscape, a restructuring cannot proceed until a defined sequence of enabling conditions is met. We are publishing this report as a practical overview for Venezuelan bondholders, but we emphasize that it is not legal or investment advice. The following framework reflects international best practices and the specific constraints applicable to Venezuela.

1. Comprehensive Political Reset, and Establishment of a Credible and Recognized Government Counterparty

Any restructuring process will require a single, internationally recognized government capable of:

- Exercising control over the Ministry of Finance, PDVSA, and the Central Bank;

- Entering into binding agreements under international law; and

- Representing the Republic in negotiations with official and private creditors.

Absent political clarity, no trustee, fiscal agent, or creditor committee can legally engage in restructuring discussions.

2. Sanctions Relief (OFAC). Licensing Framework to start negotiations to settle and issue new debt

As of now, Venezuela and PDVSA remain subject to comprehensive U.S. sanctions that prohibit:

- New debt issuance

- Debt restructuring

- Payments to creditors

- Negotiations involving U.S. persons

In order to enable a debt restructuring, OFAC must issue:

- General licenses allowing negotiations

- Specific licenses for settlement and new bond issuance

No restructuring can legally occur without this. Sanctions relief is a necessary condition for any orderly process.

3. Macro Stabilization Program. Engagement with Multilaterals (IMF, World Bank, IDB, CAF)

A credible restructuring requires a macroeconomic framework that is supported by multilateral lending institutions. This typically includes:

- Fiscal consolidation

- Exchange-rate unification

- Monetary stabilization

- Reform of the oil sector

- Institutional strengthening

The creation of a macro stabilization program provides the foundation for assessing Venezuela’s repayment capacity. We note that the IMF has engaged Venezuela in many years, and we have not yet any solid indication that the IMF is actively engaged with Venezuela. On the other hand, Venezuela is an important participant in Corporacion Andina de Fomento (CAF) and we do not rule out higher engagement in the near term from the supra to support Venezuela through a political and economic transition. A macro stabilization plan usually also includes a Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) to determine:

- The sustainable level of public debt

- Required haircuts on principal and interest

- Feasible maturity extensions

- The need for new financing

A DSA serves as the analytical basis for the restructuring proposal. A DSA for Venezuela would likely includes fiscal reform, monetary/exchange rate reform and an oil sector recovery plan.

4. Comprehensive Claim Mapping for Bonds

Another challenge in a debt restructuring for Venezuela/PDVSA is that they face a fragmented and diverse creditor constituency, including:

- Sovereign bondholders

- PDVSA bondholders

- Holders of the PDVSA 2020 (secured by CITGO shares)

- Commercial creditors

- Domestic debt holders

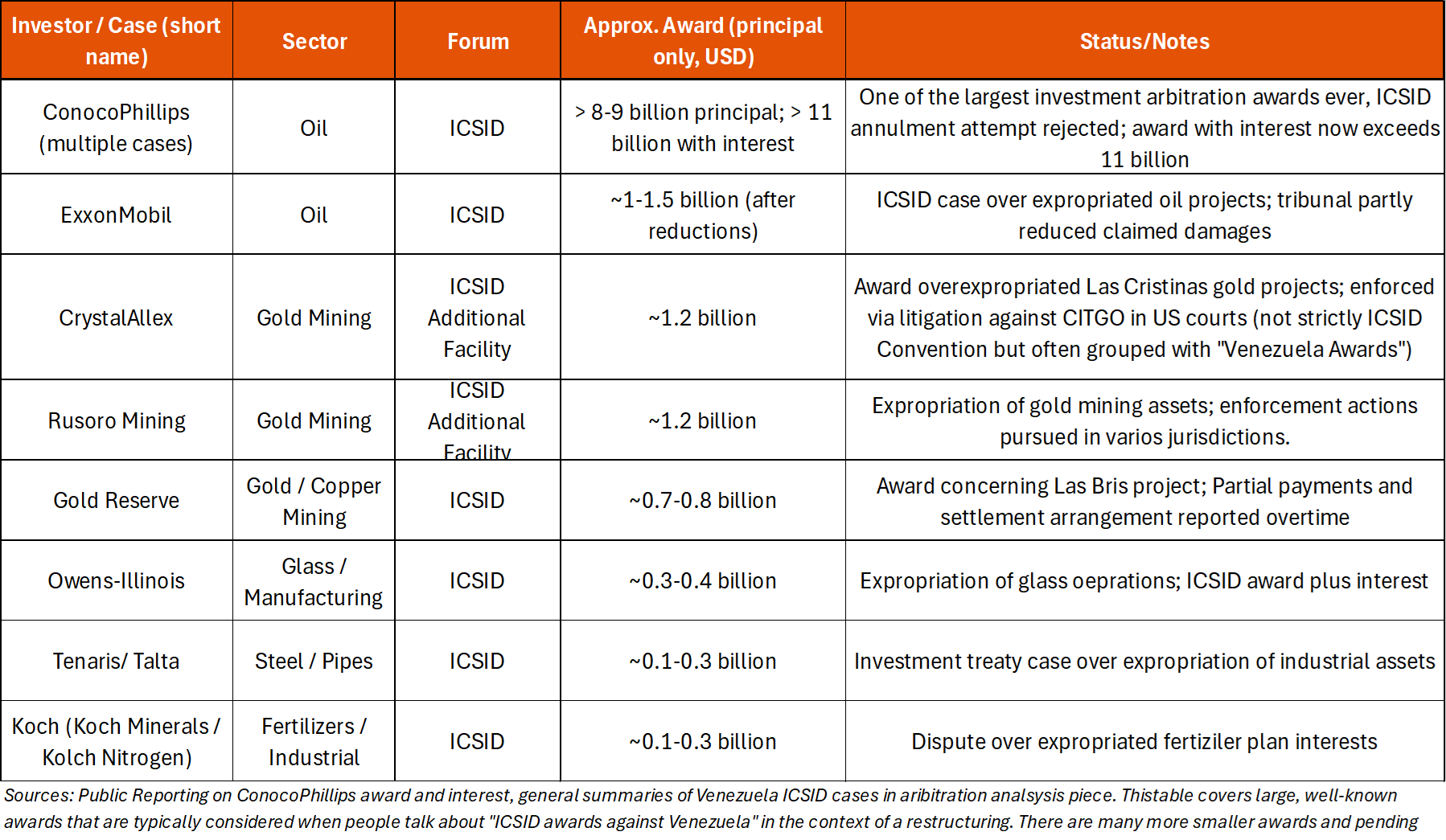

- International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes “ICSID” arbitration claimants

The last one is often overlooked, but is important to understand Venezuela’s debt and legal landscape. The ICSID is part of World Bank Group, and the claimants here matter as much as the bonds in any future restructuring. In past years, Venezuela nationalized dozens of foreign companies (oil, mining, telecoms, banking). As a result, many corporates and investors sued under bilateral investment treaties. Venezuela lost many of these cases. As a result, Venezuela now has one of the largest ICSID liabilities in the world.[2]

We note that the outstanding ICSID judgments carry several key implications:

- ICSID awards are a parallel “creditor class” which sit outside the bond contracts and Collective Action Clauses (CACs), with their own enforcement track (asset seizures, especially CITGO)

- They compete with bondholders for the same pool of assets, particularly PDVSA/CITGO, tankers, receivables, etc.

- In any realistic restructuring, these awards must be politically and financially integrated into the deal either via separate negotiated settlements, parallel restructuring instruments, or staged payments linked to oil revenues

In order to achieve anorderly restructuring of the various claims, the steps include:

- A complete registry of claims

- Classification of the various creditor groups

- A strategy for each category

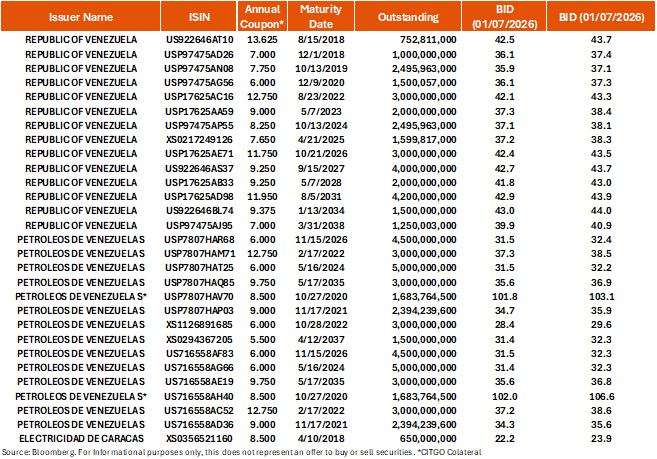

We note as well that within the international bond issuances, there are a mix of legal and structural characteristics. These differences may not be fully understood by all market participants, and could drive different in recovery values and market prices. Below we consider some factors which could drive different market prices:

- Collateralization: Most international bonds are unsecured obligations but a few have collateral, notably PDVSA 2020; we note that these collateralized bonds trade close to par

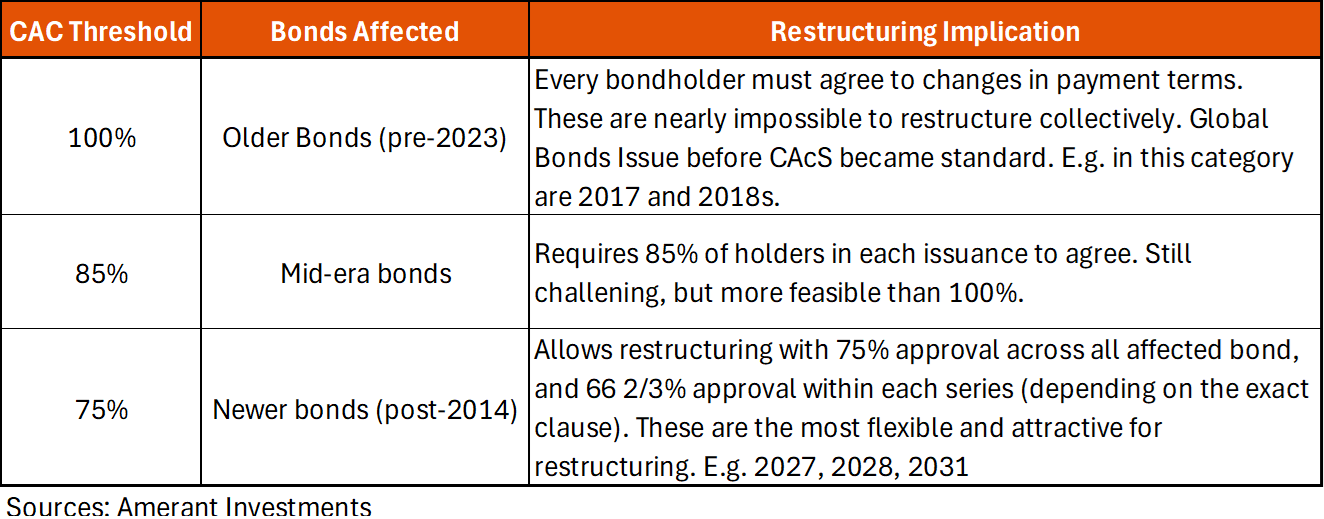

- Collective Action Clauses (CACs): Venezuelan sovereign bonds vary in how easily they can be restructured. Some require unanimous consent (100%) to change payment terms, while others need only 75% or 85%. Bonds harder to restructure tend to trade at lower prices. Most PDVSA bonds do not contain collective action clauses, meaning that a restructuring must, in theory, be done individually with each bondholder. Venezuelan sovereign bonds issued under New York law fall into three main categories based on their CAC voting thresholds:

- Original Issue Discount (OID): Certain PDVSA bonds were issued at steep discounts, which can introduce legal ambiguities and reduce investor confidence, lowering their bid prices.

- Amount Outstanding: Bonds with larger outstanding volumes may be more actively traded, affecting their bid-ask spreads and pricing.

- Investor Base: Some bonds are held by hedge funds, which may be willing to litigate or negotiate better terms, which can influence pricing dynamics

5. Collective Action Clauses Present a Challenge

The claims mapping challenge becomes acute once the issues around the CACs are fully understood. For example, bonds without CACs or with high thresholds (like 100%) are vulnerable to holdout creditors who refuse restructuring, complicating any debt resolution. Bonds with easier restructuring paths (75% CACs) tend to trade at higher prices due to better recovery prospects. Further, creditors may target bonds with no CACs for litigation, while sovereign bonds with CACs are more likely to be part of a negotiated restructuring.

In a restructuring, the governing law also matters, so bonds may be described as having a “Standard NY‑law CAC in series.” Under this framework, creditor voting happens per bond series, with each ISIN having its own “series.” A restructuring vote is held separately for each bond. There is no aggregation across different bonds, and each needs its own supermajority. We note that if the required supermajority approves the terms, all holders of that series are bound—even those who vote no.

A standard NY‑law CAC allows supermajorities to modify principal, interest, maturity, payment dates, payment currency, and acceleration/default terms. However, unlike bonds with “aggregated CACs,” a standard NY‑law series CAC cannot combine multiple bonds into one vote, bind other series, or override holdouts in other maturities. In conclusion, series‑by‑series CACs are much weaker than aggregated CACs in restructuring. Because Venezuela issued many bonds with series‑only CACs, a restructuring requires many separate votes each with its own supermajority and each vulnerable to holdouts and potentially litigated separately.

PDVSA’s restructuring presents unique challenges. The government will need to determine whether to restructure PDVSA separately and consolidate PDVSA liabilities into the sovereign, create a new operating entity (“PDVSA 2.0”), or utilize a restructuring SPV to issue new instruments with CACs.

6. Credit Committees, followed by Execution of Exchange and Conclusion

As part of the claims mapping, creditors must organize into representative committees including sovereign bondholders; PDVSA bondholders; arbitration and litigation creditors, and commercial suppliers. The government should present a comprehensive proposal, or term sheet, specifying:

- New bond maturities and coupons

- Treatment of past‑due interest (PDI)

- Haircuts on principal and interest

- Use of GDP‑ or oil‑linked instruments

- CAC structure for new instruments

- Treatment of secured and unsecured claims

The restructuring must be supported by:

- Aggregated CACs to bind all series

- Clear treatment of holdouts

- Legal opinions under New York and English law

- A mechanism for settlement and exchange

- Coordination with trustees and fiscal agents

This ensures enforceability and minimizes litigation.

Only after the multi-step process described above, and with approval by the requisite creditor majorities, would we see the defaulted instruments tendered and new bonds issued. In the final terms, we will see if past due interest PDI is capitalized or discounted. We have read reports that suggest the restructured debt could include an additional or separate issuance of a X-year zero-coupon bond to make up for all the missed interest payments since 2017.

In conclusion, an orderly restructuring of Venezuelan and PDVSA debt requires a carefully sequenced process involving political normalization, sanctions relief, macroeconomic stabilization, legal clarity, creditor coordination, and a credible restructuring proposal. Each step is interdependent; failure to satisfy any one of them risks a disorderly, protracted, and litigation‑heavy outcome.

[1] This represents an estimated figure. Venezuela stopped publishing full debt data around 2016–2017, and no comprehensive official debt bulletin has been released since then.

[2] These are not bonds — they are legal judgments.

For additional insights, be sure to check out last week’s blog post.

Definitions, sources, and disclaimers

This content is being published by Amerant Investments, Inc (Amerant Investments), a dually registered broker-dealer and investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and member of FINRA/SIPC. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill, endorsement, or approval. Amerant Investments is an affiliate of Amerant Bank.

Definitions:

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP): A comprehensive measure of U.S. economic activity. GDP is the value of the goods and services produced in the United States. The growth rate of GDP is the most popular indicator of the nation’s overall economic health. Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

- GDPNow is not an official forecast of the Atlanta Fed. Rather, it is best viewed as a running estimate of real GDP growth based on available economic data for the current measured quarter. There are no subjective adjustments made to GDPNow—the estimate is based solely on the mathematical results of the model. In particular, it does not capture the impact of COVID-19 and social mobility beyond their impact on GDP source data and relevant economic reports that have already been released. It does not anticipate their impact on forthcoming economic reports beyond the standard internal dynamics of the model.

- The Current Employment Statistics (CES) program produces detailed industry estimates of nonfarm employment, hours, and earnings of workers on payrolls. CES National Estimates produces data for the nation, and CES State and Metro Area produces estimates for all 50 States, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and about 450 metropolitan areas and divisions. Each month, CES surveys approximately 142,000 businesses and government agencies, representing approximately 689,000 individual worksites. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

- Initial Claims: An initial claim is a claim filed by an unemployed individual after a separation from an employer. The claimant requests a determination of basic eligibility for the UI program. When an initial claim is filed with a state, certain programmatic activities take place and these result in activity counts including the count of initial claims. The count of U.S. initial claims for unemployment insurance is a leading economic indicator because it is an indication of emerging labor market conditions in the country. However, these are weekly administrative data which are difficult to seasonally adjust, making the series subject to some volatility. Source: US Department of Labor (DOL).

- The Consumer Price Index (CPI): Is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. Indexes are available for the U.S. and various geographic areas. Average price data for select utility, automotive fuel, and food items are also available. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

- The national unemployment rate: Perhaps the most widely known labor market indicator, this statistic reflects the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the labor force. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

- The number of people in the labor force. This measure is the sum of the employed and the unemployed. In other words, the labor force level is the number of people who are either working or actively seeking work.Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

- Advance Monthly Sales for Retail and Food Services: Estimated monthly sales for retail and food services, adjusted and unadjusted for seasonal variations. Source: United States Census Bureau.

- Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC): Responsible for implementing Open market Operations (OMOs)–the purchase and sale of securities in the open market by a central bank—which are a key tool used by the US Federal Reserve in the implementation of monetary policy. Source: Federal Reserve.

- The Federal Funds Rate: Is the interest rate at which depository institutions trade federal funds (balances held at Federal Reserve Banks) with each other overnight. When a depository institution has surplus balances in its reserve account, it lends to other banks in need of larger balances. In simpler terms, a bank with excess cash, which is often referred to as liquidity, will lend to another bank that needs to quickly raise liquidity. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- The “core” PCE price index: Is defined as personal consumption expenditures (PCE) prices excluding food and energy prices. The core PCE price index measures the prices paid by consumers for goods and services without the volatility caused by movements in food and energy prices to reveal underlying inflation trends. Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED), Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, U.S. Census Bureau, Department of Housing and Human Development (HUD), U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), U..S Department of the Treasury, Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), U.S. Department of Commerce, data.gov, investor.gov, usa.gov, congress.gov, whitehouse.gov, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Morningstar, The International Monetary Funds (IMF), The World Bank (WB), European Central bank (ECB), Bank of Japan (BOJ), European Parliament, Eurostats, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), World health organization (WHO).

Financial Markets – Recent Prices and Yields, and Weekly, Monthly, and YTD (Table): Bloomberg, Weekly Market Data is in USD and refers to the following indices: Macro & Market Indicators: Volatility (VIX); Oil (WTI); Dollar Index (DXA); Inflation (CPI YoY); Fixed Income: All U.S. Bonds (Bloomberg Aggregate Index); Investment Grade Corporates (Bloomberg US Corporate Index); US High Yield (Bloomberg High Yield Index), Treasuries (ICE BofA Treasury Indices); Equities: U.S. Industrials (Dow Jones Industrial Average); U.S. Large Caps (S&P 500); U.S Tech Equities (Nasdaq Composite); European (MSCI Euope), Asia Pacific (MSCI AP), and Latin America Equities (MSCI LA); Sectors (S&P 500 GICS Sectors) Source: Bloomberg. Fed Funds Rate probabilities, Source: CME FedWatch Tool.

Important Disclosures:

The information provided here is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered a customized recommendation, personalized investment advice offer, or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security or investment strategy. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own situation before making any investment decision.

This information is obtained by AMTI from third-party providers from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reflective of results you can expect to achieve. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice in reaction to changes in market conditions. By using such information, you release and exonerate AMTI from any responsibility for damages, direct or indirect, that may result from such use. Consult the issuer of any investment for the most up-to-date and accurate information.

All references to performance refer to historical data. There could be benchmarks used that do not reflect the performance of funds or other products with similar objectives

Presentation does not apply in jurisdictions where its use has not been approved. Some products or strategies may be complex or unusual. Make sure you have a clear understanding of the products before investing. Investments may have different tax consequences in different jurisdictions and will depend on the circumstances. AMTI does not offer legal or tax advice, please consult your legal, CPA, or other tax professional regarding your situation.

Before investing you must consider carefully the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses of the underlying funds of your selected portfolio. Please contact AMTI to request the prospectus, private placement memorandum or other offering materials containing this and other important information. Please read these materials carefully before investing.

Not FDIC Insured | Not Bank Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Insured By Governmental Agencies | Member FINRA/SIPC, Registered Investment Advisor

Additional Risks:

- Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

- There is no assurance the Fund will pay distributions in any particular amount, if at all. Any distributions the Fund makes will be at the discretion of the Fund’s Board of Trustees

- There can be no assurance that any Fund or investment will achieve it objectives or avoid substantial losses. Actual results may vary

- The value of the investments varies and therefore the amount received at the time of sale might be higher or lower than was originally invested. Actual returns might be better or worse than the ones shown in this informative material.

- Limited liquidity: Investors should not expect to be able to sell shares regardless of how the Fund performs. Investors should consider that they may not have access to the money they invest for an extended period of time.

- Volatile markets: Because an investor may be unable to sell its shares, an investor will be unable to reduce its exposure in any market downturn

- Funds may invest in securities that are rated below investment grade by rating agencies or that would be rated below investment grade if they were rated. Below investment grade securities, which are often referred to as “junk,” have predominantly speculative characteristics with respect to the issuer’s capacity to pay interest and repay principal. They may also be illiquid and difficult to value

Please review the prospectus or related materials for further details regarding risks and other important information. For additional disclosures and other information regarding AMTI including our customer relationship summary, please visit: https://www.amerantbank.com/personal/investing/